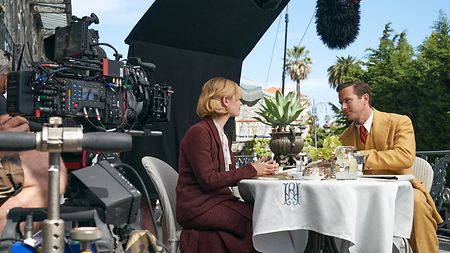

“Rebecca” tells the story of a young woman who marries a handsome widower named Maxim de Winter after a whirlwind romance in Monte Carlo. On moving into his imposing English mansion Manderley, the new Mrs. de Winter becomes increasingly traumatized by the oppressive legacy and mysterious death of Maxim’s first wife, Rebecca. Director Ben Wheatley and cinematographer Laurie Rose, BSC opted for a fresh visual approach to this new adaptation for Working Title Films and Netflix, shooting in 65 mm with ARRI Rental’s exclusive ALEXA 65 camera and DNA lenses. Rose speaks here about his equipment choices and experiences on the production.

Can you describe your working relationship with Ben and how you came to shoot “Rebecca” on the ALEXA 65?

This is our eighth project together. The first was “Down Terrace,” which was a 90-minute feature film that we shot in eight days for £6,000, back in 2008. A year later we did another one and the budgets grew, and we ended up doing four very similarly like that on the run, with about a year between them, during which we would go back to our day jobs – I was a TV cameraman and Ben was directing commercials. It was only after our fifth film together, “A Field in England,” that I gave up my day job!